With interest rates as low as they are today, it does not require much inflation to take a nominal yield gain and leave real yield pain.

For example, if an investor purchased a $1,000, 1 year U.S. Treasury Bill today, and then held it to maturity, they would realize a gain of $1.70, based on the current nominal yield of 0.17%. Though the risk of not being payed back is exceptionally low, the bill is backed by the United States government, an investor purchasing a 1 year U.S. Treasury Bill has to ask themselves; will the yield from the investment be enough to compensate me for the risk of inflation in the coming year? In other words, one year from today will $1,001.70 purchase the same amount of goods that $1,000 does today? If consumer prices increase by more than 0.17% in the next year the real yield on the purchased 1 year U.S. Treasury bill will be negative. Inflation will have eaten at the return.

It is impossible to know for certain what inflation will be one year down the road and expectations as to the rate of inflation varies from investor to investor. Today, however, it would either take exceptionally low inflation or deflation in order for an investor to come away with a positive real yield on a 1 year U.S. Treasury bill. The current low, nominal, yield of 0.17% that investors are willing to accept could be due to a few factors. First, investors may in fact believe that inflation will be low over the coming year. Second, investors may be willing to purchase a 1 year U.S. Treasury bill even if they expect inflation to be greater than 0.17%. They would do because of the relative safety of the asset. Due to the U.S. governments high credit standing the chance of not being paid back at the end of the 1 year investment period is extremely low as compared to other riskier credits.

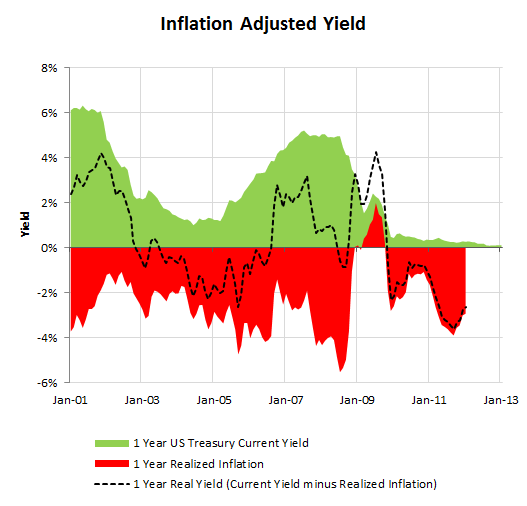

While it will only take 0.17% of consumer inflation to swamp the nominal yield of a 1 year U.S. Treasury bill today, in the past a much higher rate of inflation was required to take a positive nominal yield and create a negative real yield because interest rates were higher. In the chart below, inflation, in red, has dragged down the nominal yield, in green, on 1 year U.S. Treasury bill yields and created a negative real yield, black dashed line, about half of the time since 2001.

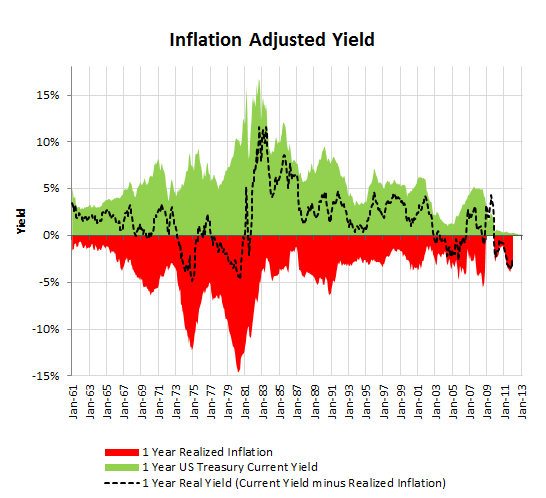

In the charts below, the 1 year U.S. Treasury bill is assumed to be purchased and held one year, until maturity. With the one year return on the security known, unless the U.S. government defaulted on the obligation, the 1 year U.S. Treasury yield is able to be plotted 1 year in advance. The inflation that will take place over the coming year is not known until the end of the period. The actual real yield also will also not be known until the end of the one year period.

A longer time frame shows that positive real yields were generally available from 1981 to 2002, a remarkable 21 year span. Conversely, there have been four periods that investors have been left with negative real yields after a year. The first two instances were during periods of high inflation, the mid 1970s and early 1980s. The second occurrences were during the last decade, when inflation was much more moderate, but interest rates, even lower. Lest, one think that high single digit real returns were easy to come by in the early 1980s, it is important to remember that the investor would have been purchasing the 1 year U.S. Treasury bill at a point in time that inflation was well over 10% and widely expected to climb even higher. The high positive real return obtained had as much to do with unexpected falling inflation as it had to do with the high nominal yield offered by the security upon issuance.